Introduction - where this blog came from, and where it's going

“I stand in between two worlds. I am at home in neither, and this makes things a little difficult for me. You artists call me bourgeois, and the bourgeois feel they ought to arrest me.” Thomas Mann, Tonio Kröger

I was brought up to believe I was a scientist, and was duly educated as one. Having done that, I then did what Mrs Thatcher wanted and went to work in industry – where thankfully I discovered that my lifelong feelings of imposture had not been lying to me.

Even as a student I had always felt a vague sense of unbelonging among my immediate contemporaries, akin no doubt to the conviction among transgender patients that they have been born into the wrong sex. Fortunately of course I was able to fool everybody long enough to get my PhD, but keeping up the pretence was too much effort after that and I fled across the border into journalism. Perhaps this personal history is why I have always felt very aware of the innate and cultural differences that mark scientists as a group.

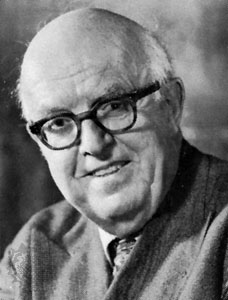

Comprehensively Snowed While assembling the ideas for this blog, my working title for it was The Three Cultures – to echo the famously titled The Two Cultures... the oft referred-to but almost completely unread 1959 Rede Lecture by novelist, scientist and statesman Charles Percy Snow. For it was with this document that angst about "science and the public", not to mention the whole useless, corrupt, self-serving circus that has since grown up about it, was first conceived.

While assembling the ideas for this blog, my working title for it was The Three Cultures – to echo the famously titled The Two Cultures... the oft referred-to but almost completely unread 1959 Rede Lecture by novelist, scientist and statesman Charles Percy Snow. For it was with this document that angst about "science and the public", not to mention the whole useless, corrupt, self-serving circus that has since grown up about it, was first conceived.

Another person on the cusp of arts and sciences, Snow was a man trapped by convention into a state of unbelonging. After a short and rather undistinguished research career, he turned with contemporary success to fiction, and the corridors of power. But he was thrice homeless. As a novelist, he hated the literary establishment. As a scientist he never recovered from his first devastating disappointment. And as a government mandarin, one gets the impression that his sympathy for democracy was largely theoretical.

The Two Cultures was a typically sweeping gesture and enjoyed great success. But although everybody working in the business of communicating science today knows the title, few have ever read the original material. As proof of this I can point to the news release that covered a recent pompous declaration (February 2003) by world scientific journal editors, which mentioned The Two Cultures in its opening sentence. These grandees of scientific editing then went on, amazingly, to attribute the seminal concept to Snow’s “eleven wonderful novels” – which clearly none of them had ever read.

Those who do read the original lecture, as well as its predecessor New Statesman article (1956) and follow-up (A second look, 1963) will find it a curious experience. Dated, insular, parochial, badly argued, threadbare – all apply, and more. Nevertheless, The Two Cultures caught the zeitgeist, and it is fair to say that the debate over science’s place in (British) Society has been comprehensively snowed ever since.

Like many who create works that develop lives of their own, Snow had an ambivalent attitude towards his essay. He bitterly regretted that he had not decided to go with his first instinct and call his lecture The rich and the poor – a more easily definable and much more serious divide, which his lecture mainly addressed. But he chose to approach his theme by way of his obsessional hatred for the literary establishment and those who cleaved to it. They, he felt, were undermining the attempts of good, honest scientific grammar-school boys like him to better the lot of their fellow man.

In the 1959 lecture he also worried: “Attempts to divide anything into two ought to be regarded with much suspicion”. Dualism – whether Manichean or Cartesian, it doesn’t matter which - encapsulates something very basic about the way our brains are wired, and Snow was sophisticated enough to know that giving in to it is too easy, and should be resisted. I very much wish he had, and I think he did too.

Arty public-school toffs vs grammar-school oiks

Snow’s concern – in brief – was that Britain was governed by public schoolboys whose education was all literary and historical (and I mean to include somewhere in this blog a look at how the famous son of a Victorian public school headmaster felt about the issue of “arts versus sciences”, at a time when the natural sciences had their tails up).

But, to stay with Snow for the time being, he asserted that the effect of this arts hegemony was to put the reins of power into the wrong hands in a scientific age. He recognised that this was the fault of a peculiarly English education system that made understanding between scientists and non-scientists worse by forcing children to specialise too early. He recognised that the roots of this lay deep in class-ridden British society, the skewed aspirations that result from it, and the baleful influence of the admissions requirements of Oxford and Cambridge universities. In this he was undoubtedly right. But Snow’s caricatures - and the tendentiousness of his assertions and examples - seem absurd today. His portrait of the typical scientist (born in the progressivist atmosphere of the 1930s) puts one uncomfortably in mind of a Leni Riefenstahl propaganda film on the one hand and an issue of Health and Efficiency on the other. Scientists, said Snow, are “steadily heterosexual” folk displaying great moral health, who put the collective welfare of humanity first, and who apply their commonsensical materialistic view to bettering the lot of the underprivileged.

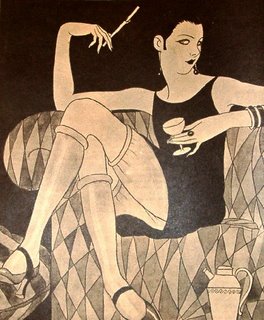

In this he was undoubtedly right. But Snow’s caricatures - and the tendentiousness of his assertions and examples - seem absurd today. His portrait of the typical scientist (born in the progressivist atmosphere of the 1930s) puts one uncomfortably in mind of a Leni Riefenstahl propaganda film on the one hand and an issue of Health and Efficiency on the other. Scientists, said Snow, are “steadily heterosexual” folk displaying great moral health, who put the collective welfare of humanity first, and who apply their commonsensical materialistic view to bettering the lot of the underprivileged. Literary intellectuals on the other hand, come straight out of Proust; all rouge, absinthe and cocktail cigarettes. Literary men (Snow’s world is almost exclusively masculine) had more of the “feline and oblique” about them, he wrote (1956). They cared more for themselves and their small coteries than for the world as a whole. They sniffed superciliously about what they saw as the empty materialism of technological progress, while more than half the world starved and could not afford such nose-holding.

Literary intellectuals on the other hand, come straight out of Proust; all rouge, absinthe and cocktail cigarettes. Literary men (Snow’s world is almost exclusively masculine) had more of the “feline and oblique” about them, he wrote (1956). They cared more for themselves and their small coteries than for the world as a whole. They sniffed superciliously about what they saw as the empty materialism of technological progress, while more than half the world starved and could not afford such nose-holding.

Stereotypes are powerful stuff, and can be very revealing (though more about their authors, as a rule). Perhaps I should be wary of criticising Snow’s, since this blog indulges in more than a few of its own. However, as mine are considerably less flattering to scientists than Snow’s, they are perhaps more likely to fall nearer the truth.

Even in insular, bourgeois 1959 Britain, there were those who found Snow’s notion that the world was somehow run from the louche salons of Chelsea, or that our failure to embrace the Third World was the fault of luddite poets and literary critics, or that the way in which white middle-class males were educated constituted the most important divide in intellectual culture, laughable. While Snow condemned literary intellectuals for failing to embrace progress (in which so much political capital was then invested, thanks largely to Snow himself), his own hankering after a mythical unified national culture was no less nostalgic than that of Victorian literary men for a pre-industrial age peopled by scholar gypsies. Both were grasping for a deeper myth – the very notion of a “unified culture”.

Our world now strives (or so it says) to embrace diversity. Within that diversity, the cultural split between the scientifically literate and everyone else seems no longer to amount to much. Except, I fear, to scientists, who partly thanks to Snow now think of themselves as one half of something called culture – a piece of monstrous self-aggrandisement that does them no credit and even less service. You hear this belief expressed most starkly when eminent scientists, having elected themselves spokespersons for the whole enterprise, bemoan the fact that while the Sunday Times may devote entire supplements to “the arts”, it does not publish an equivalent one devoted to science.

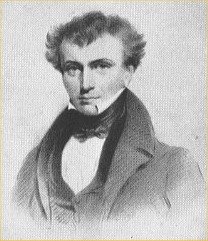

Just like Snow’s central thesis, it is a little amazing that more people do not see the absurdity of this. Why does it occur to so few people that the Arts exist, very largely, to communicate, give pleasure and be accessible? Science exists for none of these reasons and is in no way equivalent. The reason lies in a neat example of how words and ideas do not exist independently (a theme I shall return to frequently in this blog, I feel sure). The terms “science” and “scientist” - meaning the pursuit of factual knowledge of the natural world and one who seeks it - were given to the English language by the 19th Century Cambridge polymath William Whewell (1794-1866). We now suffer a semantic distinction in English that simply does not apply in the rest of Europe, where the term “science” or its equivalent tends more to refer to all forms of organised knowledge. But even this is not the whole story. The strictures of Anglophony are as nothing compared to those of Britishness. For, just as academics are nearly always worse communicators than industrial scientists (who are trained to do it well because it means money), there is hardly any innate quality predisposing scientists to being poor communicators that is not hugely exacerbated by being British.

The reason lies in a neat example of how words and ideas do not exist independently (a theme I shall return to frequently in this blog, I feel sure). The terms “science” and “scientist” - meaning the pursuit of factual knowledge of the natural world and one who seeks it - were given to the English language by the 19th Century Cambridge polymath William Whewell (1794-1866). We now suffer a semantic distinction in English that simply does not apply in the rest of Europe, where the term “science” or its equivalent tends more to refer to all forms of organised knowledge. But even this is not the whole story. The strictures of Anglophony are as nothing compared to those of Britishness. For, just as academics are nearly always worse communicators than industrial scientists (who are trained to do it well because it means money), there is hardly any innate quality predisposing scientists to being poor communicators that is not hugely exacerbated by being British.

British disease, British unease

Snow acknowledged that he was speaking from a British perspective. He saw that our university-dominated, early specializing education system deepened the divide between science and humanities. In addition to everything else, British scientists are also more likely to despise popularisation; to be defensive, deferential, prey to academic snobbery, subject to crippling ageism. They have been rather less likely (than US scientists, particularly) to work in big teams - though perhaps this effect is diminishing. Hence they have tended to become more isolated, less socially practised and more peculiar. They are certainly much more likely to be embarrassed in front of a camera or a microphone.

The Island Race gets the worst of all worlds. Its scientists feel the need to justify themselves acutely , while continental scientists (in common with continental intellectuals generally) are self-confident enough not to. However we also lack the easygoing personal presentational skills that Americans seem to imbibe with mother’s milk, and to suffer the impediment of social structures that conspire to make recovery in the short term unlikely.

But the avowed Britishness of The Two Cultures is largely lost on the British who, like scientists, don’t realise how odd they are as a group because they don’t know any better. The British tend to react with shock and surprise when they find that a parallel debate about the position of science in culture is generally not happening - to anything like the same degree - in the rest of Europe. This business of "unrecognised peculiarity" will be another abiding theme of this blog.

A notable post-Snow phenomenon has been the attempt to demonstrate that “scientists are just like everyone else”. I would agree wholeheartedly that scientists are not robots, but the idea that they are just like everyone else is not only patently untrue but does them a grave disservice. Nobody is likely to assert that poets are “just like everyone else”, or to believe that a poet who is, is likely to be any good. Scientists are, in fact, very special, unusual people – who for that reason have commanded my lifelong interest and respect. In a world that embraces diversity, they should be out-and-proud about their differences - while at the same time accepting that distinctive differences also bring peculiar limitations. These limitations must be avowed before they can be addressed.

As a problem, Snow’s “two cultures” was, and is, chimerical. Moreover, it has led us down some very long garden paths that had better gone untravelled. This blog seeks to explore those byways. It seeks to explain where I believe scientists and their cheerleaders have gone wrong. It sets out to describe the embedded ideas and fixed mindsets that give scientists their curiously skewed perceptions and unrealistic expectations of the world. And it seeks to encourage a different approach, based on rather old-fashioned journalistic and PR know-how.

It also seeks to explore scientists’ trademark characteristics of mind. From these, it attempts to explain how scientists’ anxieties have allowed a huge and almost entirely ineffectual “third culture” to grow up around them, of unskilled propagandists and academic parasites and a circus of conferences and talking shops that have become (for those old enough to remember it) a Tanganyika Ground Nut Scheme de nos jours.

London, July 2006

The big plan...

I wrote this blog backwards, in a series of ten polemical "fits", over a space of a few fevered days. So the first written "fit" was Number 10, and this Introduction forms the latest entry by date. This means the blog can now be read like a book from beginning to end.

The entries that follow are:

- Fit 1 – Not like us or, why the things that make scientists good at being scientists may not be universal blessings

- Fit 2 – Little helpers or, the tale of the professor’s lovely assistant

- Fit 3 – Climbing Mount Impossible or, why opening your mind to incredible notions is not always a good idea

- Fit 4: - Oh no they love us after all or, why scientists secretly rather like feeling neglected and miserable

- Fit 5: - Public relations is not education or, why things seem obvious when you don't know anything about them

- Fit 6: - Mayflies & termites or, what makes science different

- Fit 7: - Fun will now commence or, the curse of organised rejoicing

- Fit 8: - Waiting in a row or, all eager for the treat

- Fit 9 - It’s official or, the kiss of death

- Fit 10: - Getting real or, why it’s really a lot simpler than we imagine

1 Comments:

message18, We sale [url=http://www.1up.com/do/my1Up?publicUserId=6037055]valium without prescription[/url], xnji, Guarante lowest prices is here, buy [url=http://osdir.com/ml/scsi/2003-11/msg00063.html]valium no prescription[/url] online.

Post a Comment

<< Home