"The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars

But in ourselves, that we are underlings."

Shakespeare, Julius Caesar

For a world so dependent upon science and technology, you would expect to see scientists everywhere. Wherever people congregate for everyday reasons unconnected with who they are and what they do - in bars, clubs, waiting rooms, foyers, bank queues and massage parlours – throw a stick and five times out of ten, you should surely hit a scientist. Strangely, though, this is not the case.

According to the Office of National Statistics Labour Force Survey for 2001, within the UK working population, just over 1.8 million people hold qualifications in science or engineering. If we accept that in total there are about 58 million people in the UK, that makes just about 3% - about 20 times the number of people in prison, but only half the minimum estimate for the number of Class A drug-users.

And don’t forget, that figure of 1.8 million is just for those who hold a qualification. Most people qualified in science are not scientists by profession – like me, for example. Although even fewer philosophy students go on to be philosophers, science degrees are not necessarily “vocational” either. Most are the passport to something else, like accountancy. There is no shame in this. Arguably, scientists who don't work in science do science more good than those who do. But it is clear that the world just doesn’t need that many scientists to be scientists.

Even if we were to add in retired qualified scientists and technologists, we would be left with an unknowable but considerably smaller number of folk who wear, or have once worn, the white coat. Such people may comprise only 1% of the total UK population. By contrast, 3 million people are registered members of Bingo clubs, while about 5 million belong to UK badminton racquets clubs.

I don’t know about you, but I expect to go to my grave not knowing anyone who plays either bingo or badminton, let alone belongs to a club dedicated to either. Despite living in Stoke Newington I don’t even know any Class A drug-users. For this reason, I believe it fair to say that most people will exit the mortal coil never having met a working scientist. This is very significant. Just as you can explain a lot of things about Britain by the fact that it is an island (and more about that later) you can explain a lot about scientists by this curious discrepancy. Scientists are not a political entity: they are few, divided and together have little influence in the ballot box. By contrast, the fruits of what they do are all-pervadingly powerful. This, I believe, lies at the root of the continuing incomprehension among scientists over their position in society, over society’s perception of them, and the value placed by society on what they do.

Birds of a feather

You don’t have to know the statistics to appreciate that scientists must be pretty rare birds – there is qualitative evidence too.

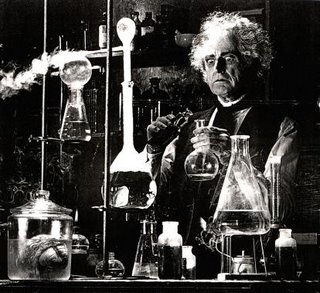

Scientists themselves would be the first to agree that portrayals of them on TV and in films are always wildly unrealistic. But then so are most portrayals of musicians, journalists, violinmakers and others whose numbers are so low that most people never meet one. Many scientists sneer at the media for this, and fret about how it may be damaging their image.

I do not. Clichés tell you a lot about the people who create them. The portrayal of minority professions like scientists is enlightening about attitudes, precisely because those images are unconstrained by reality. This is not “misperception”. These portraits are not based on perception: they are based on expectation – on how the audience thinks such a character should be. And no profession recognises or likes its fictional image.

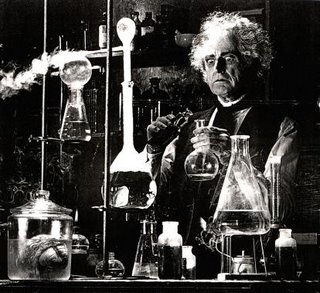

In this respect, scientists are just like everyone else. However it is a sign of deep insecurity that they take it so much more badly, and worry more about being portrayed as “mad and bad” than, say, journalists do. Now you might offer, by way of explanation, that this is because of outrage at the injustice. CP Snow asserted that typical scientists think of themselves as being on the side of the angels. Perhaps the unfairness of the Dr Frankenstein accusation really hurts.

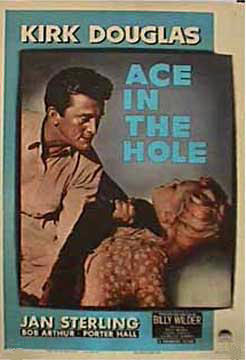

Well, possibly. Scientists are just like everyone else in the sense that their capacity for self-delusion is infinite, too. My experience is that scientists are no nobler and have no more (or less) belief in the rightness and importance of what they do than journalists. Journalists also think of themselves as working to the common good, and take what they do very seriously indeed. They may not like the way the public chooses to see them (picture - Kirk Douglas as manipulative and unscrupulous Chuck Tatum in the 1951 classic (Paramount)), but they don’t whinge about it.

Like all rare beings, scientists huddle together for warmth and security. In the days when I pretended to be a scientist, I studied the way encrusting organisms, like barnacles and oysters, choose the place where they should settle for life. This is a big decision for a larval encruster, for whom location is as important for success as it is for any newsagent. If the larva gets the location wrong, the adult – which cannot move once it is fixed – will die.

Not surprisingly therefore, the presence of others of its kind, and even the attachment scars of long-dead forebears, is a powerful recommendation for a site to settle. For this reason, most encrusting organisms tend to cluster – even generation after generation. As the old saw has it - the acorn rarely falls far from the tree. Even for an oyster or a barnacle, the presence of attachment scars renders the decision of whether to settle much simpler. There are no spectra, just yes or no; no weighing up of environmental pros and cons required. Dad liked this place, so will I. Dad did all right here, and what’s good enough for Dad…

It is easy to construct sociobiological arguments why an analogous pattern should emerge among human beings. If your parents are good at something, you begin with the two advantages. Your genetics are likely to predispose you: if dad was good at fishing, you probably will be too. Secondly, you have nurture on your side because you start learning young. So it is that dynasties - in science as well as in business, media and the arts - grow up.

Like any other group drawn together by common aptitudes and interests, scientists grow up together, learn together, marry each other and grow old together. Their offspring stand a high chance of wearing, in adulthood, hand-me-down white coats or hard hats bequeathed by their proud forebears.

What this fact of life achieves is to reinforce the already present tendency for scientists’ perception of the world to be akin to that of – I am tempted to say a barnacle – but I shall say instead that of a ghetto-dweller.

It is easy to see how this can set up a mental conflict. From inside, it looks to scientists as though scientists are everywhere, for all to see. Yet, views of scientists evidently persist that are wildly at variance with reality – and “reality” is a concept very dear to the scientific mind; more of which below. They begin to fret.

Why are WE not powerful like science is?

They look around at the pervasive influence of science and technology. They see people who are delighted to accept the conveniences, but are absurdly over-sensitive about the negligible harm that could possibly arise from things that seem to bring them no benefit. Scientists feel ignored, misunderstood, by-passed and powerless. Once again, the world of non-scientific humans seems even more illogical and incomprehensible than it already did. Why don’t science and technology exert more influence over planning decisions? Why are scientists not believed? Whence this pervasive suspicion? Why does not science have a greater influence over the media and political agenda?

In all generations, but especially since Snow, scientists are apt to conclude that there must be a conspiracy at work. Perhaps it’s those louche but influential artistic degenerates in Chelsea (see the Introduction), or whatever the updated version of Lord Snow’s caricature might be; people who are better connected; who are more gregarious, perhaps; who can do all that small-talk stuff and get invited to parties. And thus, scientists find themselves gloomily participating in their own stereotype; tacitly admitting that they are precisely the isolated, socially inept people they often appear to be in films.

In all generations, but especially since Snow, scientists are apt to conclude that there must be a conspiracy at work. Perhaps it’s those louche but influential artistic degenerates in Chelsea (see the Introduction), or whatever the updated version of Lord Snow’s caricature might be; people who are better connected; who are more gregarious, perhaps; who can do all that small-talk stuff and get invited to parties. And thus, scientists find themselves gloomily participating in their own stereotype; tacitly admitting that they are precisely the isolated, socially inept people they often appear to be in films.

Image: © Hoover Candy Group

The truth is very different. As we shall see, scientists are far from being generally misunderstood and reviled. Science is very far indeed from being politically powerless – it’s merely weak in the ballot box, which is a different thing. Science does exert a lot of influence over the planning, political and media agendas – it’s just that some scientists would not be satisfied until it became the only - or at least the dominant - influence. (The unreality of scientists’ expectations will be explored in Fit 3. )

But we have come far enough to draw a preliminary conclusion. In response to the question: “what are scientists like?” we can say that they are few, that like other professions they tend to cluster together, and that they don’t recognise themselves in the way they are portrayed. They think (characteristically) that portrayals should reflect “reality” as they would define it. But in fact, portrayals only reflect the reality of expectation.

Charles Percy Snow had clear ideas about how scientists ought to be, and he devoted quote a lot of The Two Cultures to giving his audience the benefit of it. The white coats have attracted a few stains since then, and his high-minded, disciplined, puritanical secular saints, motivated by the improvement of the human condition, seem ludicrous today. A liking for flattery is yet another thing that makes scientists just like everyone else.

However, faced with the need to earn money and get on in life, scientists are also part of the ugly world - it’s just that the low strategies they must adopt to survive in it are, naturally, adapted to their own piece of country. For an estate agent, one strategy for getting to the top probably involves dressing in a suit and wearing cufflinks. For a scientist, it will not; however it might well involve suppressing doubts about a dominant theory because that theory was erected by the grandees who now sit on peer review committees, grant-awarding bodies and appointment panels.

In both senses of the expression, these aspects of scientific behaviour are not enlightening. We all express feebleness in the face of the human condition, and we do it in our own ways according to our circumstances. What I am trying to get at are the things that make scientists different. Why? Because in the end we all make our own luck and get precisely the press we deserve. If anything needs fixing in this area, scientists have to look inside themselves for it. And I strongly suspect that the things that make scientists good at being scientists are the same things that make them bad at promoting themselves, communicating with non-scientists, and getting other people on their side.

What I now present is one answer to the question “what are scientists like?” phrased in the form of a negative horoscope for the 13th sign of the Zodiac – the scientist.

I’m not paranoid; it’s just that everyone’s against me

It is the major premise of this blog that, just as the fear of crime is said to be a greater social evil than crime itself, scientists’ own problems – which lie well within their power to change or adapt to – are much greater than any threat “out there” among the (largely imaginary) conspirators. That misplaced suspicion leads scientists to adopt misdirected strategies – almost always for other people than themselves to adopt, naturally – to improve the situation.

This blog contends that most of the “problem” is imaginary, or based on expectations that need a reality check. Once these bogeys are exorcised, the real problems that are left behind as the phantasms fade away, lie with scientists themselves. Unless scientists wake up to this, large amounts of their time (and money) will go on being wasted. For, as the last 20 years have shown (to my satisfaction at least) although plenty of other people are prepared to “help scientists get their message across” as they would say, such folk usually end up helping themselves and achieving absolutely nothing.

Establishing that scientists are in many important ways different from ordinary people runs counter to one of the most conspicuous PR efforts made by scientists and their cheerleaders in recent years; namely, to try to deny their uniqueness and convince the public of the complete opposite. This movement reached its zenith in the 1980s, when everyone (not just scientists) was more than usually concerned about their image.

Scientists in the 1980s looked upon their stereotype and despaired. Then, extending arguments that were already gaining currency at that time about social embeddedness – the notion that scientists do not work in a pure vacuum isolated from their historical and social context – commentators began to write about what warm and cuddly people scientists were, too. Not only was science not conducted in isolation from society; it was carried on by intuitive and creative folk who were most definitely not robots, not heartless and cruel, and most of all, not peculiar - just like everyone else, in fact. And you may ask: “If people are happy with the notion, where is the harm?

- First, if it isn’t true, it won’t wash. Contrary to popular belief, successful Public Relations (which is what this is) relies on truth - and the one thing that always gets you found out is a lie.

- Second, why should scientists not wish to be seen as special and different? Why would scientists not wish their unique qualities to be recognised and respected?

The key to “why not” lies in respect. Some scientists – Darwin, Newton, Einstein - are scene-shifters and change our world forever. But the rest are for the most part deeply conformist in outlook and sensitive to what other scientists think of them. This curious fact comes about because science is overtly collective - which makes it unique among human intellectual endeavours. But collectivity, while it has many positive aspects, also has its down side.

Mob mentality

Science journalists are fond of noting how many scientists, when they think they are addressing the public down a microphone, are really thinking about how their performance will play with their colleagues, so terrified are they of being thought idiotic or publicity-seeking. That is one reason why “standing out from the crowd” is unpopular with scientists – they have a mob mentality.

But even more basic than this is the simple dread felt by the swotty kid who tires of getting his satchel kicked around the playground. He wants mostly to blend into the general background (while enjoying, if possible, star status among like-minded friends in the Bus-spotting Club). Science provides an outlet for such people (classically, men) with low social skills and obsessive attention to detail in limited fields of inquiry; people who fall at the mild end of the so-called autism spectrum, and are said to display Asperger’s Syndrome.

Characteristics of Asperger’s Syndrome are relatively common in the population, but are much more common in some sections than others. The characteristics of a typical Asperger’s patient occur ten times as often in men than women, and the figure may may be even higher than that. Prof. Simon Baron-Cohen, a clinical psychologist at Cambridge University, has found that Cambridge undergraduates in science and technology were much more likely to show Asperger traits than those in the arts and humanities. Mathematicians come top of the Asperger league, followed by engineers, computer scientists and physicists, and with biologists showing the lowest tendency. Baron-Cohen has since written a book about his belief that Asperger’s Syndrome is an extreme version of typical "psychological maleness".

Characteristics of Asperger’s Syndrome are relatively common in the population, but are much more common in some sections than others. The characteristics of a typical Asperger’s patient occur ten times as often in men than women, and the figure may may be even higher than that. Prof. Simon Baron-Cohen, a clinical psychologist at Cambridge University, has found that Cambridge undergraduates in science and technology were much more likely to show Asperger traits than those in the arts and humanities. Mathematicians come top of the Asperger league, followed by engineers, computer scientists and physicists, and with biologists showing the lowest tendency. Baron-Cohen has since written a book about his belief that Asperger’s Syndrome is an extreme version of typical "psychological maleness".

The typical traits of an Asperger’s character involve finding social situations difficult, a low ability to make small talk, a very high ability in picking up details and facts, a tendency to find it hard to know what others are feeling, a very high ability to concentrate for long periods on the same thing, a tendency to have strong but narrow interests, to like routines, to do things inflexibly and repetitively, and – unsurprisingly perhaps - a certain lack of success in making friends easily.

It is not hard to see why such mental characteristics may be real advantages to a scientist or computer technologist, but disadvantages in, for example, a career in public relations. Taking all these things together, such mental attitudes and social conditioning can – in other contexts - be highly disadvantageous. They lead scientists to shy from the world and take refuge in delicious and maudlin self-pity. Sometimes I fear that this is a condition from which scientists collectively will never break out. It is one of my main reasons for writing this blog.

Meet my friend Thing

Realising that most people are not very interested in things and ideas comes early in the career of any would-be science writer. In my case, the scales fell when a publisher handed me back a book proposal (about geology) and said: “I am sure this would be a very good book. The referees were all positive about it. I agree that we would be well placed to publish it. But we won’t. We won’t because there are no people in it. People, you see, are interested in people”.

He might have added, “…and most people, unlike scientists in the main, live their lives entirely through their emotions and sensations”, because turning science back into something about people that will excite the emotions and the senses is what the professional science populariser’s job largely consists of.

At that time I had just emerged from the oil business, where I had been involved in technical writing – writing scientific reports as a consultant to various client companies. This is a form of popularisation, but it is not the Daily Mail. Though the folk you write for may not be scientists, they are highly motivated readers - they have dollar signs in their eyes. All a "technical writer" must do is translate jargon.

So I remember this interview as something of a personal epiphany. Not only did it dawn on me that as a popular writer, my readers must always be the focus of everything I write; I also realised that, as a scientist, I had been gradually retreating from life all my career.

I had begun as a zoologist. Then, plants seemed more interesting and I veered botanical. Then fossil animals claimed my attention and I became a geologist. Then fossil plants seemed to offer the sort of challenge I was after. Finally, in the oil business and earning money, I found that I had developed an overweening desire to understand the chemistry that drives the processes of solution and precipitation during the post-burial history of limestones.

Lots of bucks there, but not a lot of life.

Chemists would undoubtedly view it differently, but this drift from the very alive through the once alive to the inanimate, marked an act of retreat; of craving for the safety of controlled conditions and predictability. It seemed that the deader things were, the more I liked it.

I had already decided that my scientific career had been more or less a sham, conducted by someone whose talent, if he had any, lay with words – a memory for which (combined with a knack for literary imitation) had enabled him to carry off the white coat long enough to fool a university into giving him a doctorate. But now, facing the grim reality of work, I had a fright. I suffered that mid-20s crisis that sometimes grips people who leave the congenial world of education to find themselves emerging from a door in a back alley on the wrong side of town, surrounded by thugs.

I ran away to the circus and became a science journalist.

"...Awkward at parties, shy with strangers, deficient in irony - they have had no choice but to turn their attention to the close study of everyday objects."

Fran Lebowitz, Metropolitan Life (1976)

Specialist journalists (at least on UK papers) are not excused the need to make their stories relevant to the everyday lives of their readers. I am easily (alas) old enough to remember when an education specialist for a worthy broadsheet like The Independent could bash out a 400-word scoop on some arcane policy shift in a dispute between university funding bodies and vice-chancellors over the Dual Support System for university research. I know because I used to help them write them.

There are relatively few such ghettoes left in newspapers these days and all news must fight for its right to live in the pages alongside everything else. Today’s news editor will throw your 400 erudite words back with the cry: “Where are the students/lecturers/parents in this garbage?” In other words - like the man said - people are interested in people.

But the real business of science is things and ideas, not people, emotions and sensuality; and what makes scientists unusual is the fact that they are happier with things that way. I have felt the pull, so I know. The world of things and ideas – the world of science – embodies simplicity and safety. Things are manipulable, facts testable, behaviour predictable. This is a world where, the more you understand, the more predictable everything becomes because the rules don’t change. What’s true today is true tomorrow. Such reliability is what makes science powerful. It is also what makes it safe. It doesn’t let you down.

It’s not only scientists who have this unusual penchant for things over people. All academics and intellectuals are to some extent wired up the same way, to a greater degree than the average fare-payer on the Clapham omnibus. It’s just that scientists are more closed off because of the nature of their subject.

The ideas of a literary critic, for example, about a thing called a novel are more accessible to the layperson because a human being with a life story wrote the novel; the novel is a tale about fictional people’s lives, and is itself intended as an act of accessible communication. Scientists, by contrast, study things that really are just things. And some of their ideas are not even rooted in everyday objects. This natural penchant may not preclude an interest in people, but as usual there tends to be a spectrum. And scientists tend to be nearer the other end of it than most of us.

Taking the epistemology

Scientists do not lavish much time on the philosophy of knowledge – one more characteristic that they do share with the rest of humanity. When Thomas Henry Huxley glibly (and rather misleadingly) defined science as organised common sense, he was reflecting an attitude of mind among researchers, not describing science itself. Actually, much of what scientists discover is completely contrary to common sense. But scientists do take a straightforward approach to reality and truth that is, basically, commonsense. If they have ever heard of it, scientists applaud Dr Johnson’s footballing proof of the true existence of material things. The scientific method gives them all the philosophy they want.

Scientists do not lavish much time on the philosophy of knowledge – one more characteristic that they do share with the rest of humanity. When Thomas Henry Huxley glibly (and rather misleadingly) defined science as organised common sense, he was reflecting an attitude of mind among researchers, not describing science itself. Actually, much of what scientists discover is completely contrary to common sense. But scientists do take a straightforward approach to reality and truth that is, basically, commonsense. If they have ever heard of it, scientists applaud Dr Johnson’s footballing proof of the true existence of material things. The scientific method gives them all the philosophy they want.

Scientists believe in an objective truth. They look for knowledge that is self-evidently true because it works and can be used as a basis for prediction. Most scientists envisage their explanations as ever-nearing approximations to this absolute truth. Newton is fine as far as he goes, but Einstein is better and one day someone else will better Einstein.

But by and large, workaday scientists just think of themselves as finding out what is. And for some it is a small step from this approach to the belief that only science can provide valid knowledge at all – but more of that below. First, I want to look at how scientists go about explaining what they have found by putting it in words.

Having discovered what “is”, scientists believe they should express it directly, and unambiguously in a manner that is style-free. They want to say only what they mean, and to mean only one thing at a time. Their approach to language is quite the opposite of, say the literary critic, for whom the what (the idea being communicated) cannot be separated from the how of the language in which it is put. For scientists, there is complete distinction between what is being said, and the means by which it is expressed. For those who believe in the existence of ideal and external truth, the idea and the word exist independently.

Working alongside scientists as a journalist, or better still as co-editor of a publication, you quickly discover that this desire, crystallised in the mannerisms and conventions of their chosen literary form the scientific paper, is very deeply ingrained.

The scientific paper is a work of fiction that presents the process of scientific discovery back to front. After a proper contextual introduction, scientific authors adduce observational evidence, consider multiple hypotheses, and then reject all but one, which emerges at the other end like a newly minted coin. The form reinforces the false notion that the scientific method is a handle-turning process like a calculating engine.

But all scientists know that what really happens is nothing like that. The true process goes more like this. Scientist observes something odd. Scientist has momentary flash of insight, in which scientist sees answer perfectly. Scientist then goes around amassing evidence to support guessed conclusion. Finally, scientist turns whole process on head, and pretends it was all deduction.

For those who might not recognise it from this oversimple account, the process is called “hypothetico-deductive” as defined by William Whewell, whom we have met already.

It is odd that the revered scientific method – which is what we are talking about - is enforced by the dictates of a fictional form. The actual scientific process is intuitive; but the method of explication is what underscores science’s verifiability. This is more than window-dressing, yet it is actually applied in the perspiration phase, the bit scientists generally hate, not at inspiration – the moment they all crave.

This crucially important literary form demands that scientists write in simple, straightforward objective language. Of course this is rarely the case, because of jargon (which cannot be avoided yet which could be avoided much more than it is). The tone is neutral, impersonal, divorced from the messiness of how things actually happened, and of course, aimed at telling the story deductively, one thing at a time, without confusion or ambiguity. These literary tics are also, coincidentally, what makes nearly all scientific papers deadly to read, since the impersonal expressed in the passive voice are unmistakable hallmarks of truly bad literary style. Scientists generally think in black-and-white, and write in grey.

Conveyancing fact

But for scientists, communication means what I call “conveyancing fact”, and doing so impersonally and unemotionally, with all excitement rigorously expunged. Just as their penchant for safety and predictability can make them prefer the world of things, scientists’ literary habits reinforce another interpersonal shortcoming often observed among them. Scientists can be rather bad at picking up “metamessage” – information hidden in the main signal.

This talent is sometimes called “reading people”, since very often in the messy world of human beings the most important stuff to know is conveyed in metamessage. To scientists, however, metamessage is ambiguity – noise in the signal; an impurity, that needs refining out. The idea that real writers may deliberately layer their meanings to convey many things at the same time; that much of this information is often not factual at all, and that this, too, constitutes communication - is alien to them.

Their colourless, utilitarian approach to expression does not improve scientists’ chances of communicating what they do to the public. It is very difficult to learn to write in more than one manner, especially if your very thought-processes, engendered by your genetics and enhanced by your nurture within the scientific ghetto, cry out together against it.

A scientist friend of mine, who also chafes at these conventions but has to live within them, once asked me about a sentence in one of his papers beginning: “Numerical experiments suggest that”. Alas, the journal’s US-based scientific editors had objected to this because in their view an interpretation was being given - numbers themselves, after all “suggest” nothing – and demanded a rewrite to reflect that. Hence he was left with having to rephrase his shorter, more lively words with the appalling “Results of the numerical experiments are interpreted by the authors as suggesting that…” to satisfy his pedantic referees (though there is a long history in US science about the separation of fact from interpretation, about which books have been written). I suggested he say: “We interpret the results of our numerical experiments…” but that, being in the active voice and good writing, also runs counter to the scientific cult of impersonality.

This is the sort of stylistic sterility that scientists find themselves up against when they write for publication. Examine any of the works of the most successful scientific communicators – I would suggest Richard Fortey and Stephen Jay Gould – and you will see that they owe their stylistic success to the fact that they have shucked the surly bonds of science’s arid, linear, literal and monothematic stylistic constraints.

Lastly, habitual literalness of mind (which comes as a job lot with their concern for what is, and its impersonal expression) further exacerbates scientists’ problems. For one thing, it means they tend to underestimate the public’s ability to discount - or at least qualify - what they see, for example, in the media. This also goes some way towards explaining why scientists react so badly to what they see as unhelpful stereotyping. Scientists have an unfortunate tendency to think that such evidence has much more persuasive power than it really has. Ordinary folk have a greater ability to detect and discount nonsense than intellectuals give them credit for.

Method acting

However post facto the scientific method is, and however epistemologically threadbare it can sometimes seem to the sophisticated, scientists are very proud of it. In fact, they tend to be a little too proud of it. As we have seen, this is especially true in Anglophone countries because of the restricted meaning of the term “science” in our language. Alas the word is therefore more easily appropriated in English by what I (and others) have identified as a baleful tendency to strut among some scientists and their self-appointed spokespersons.

Professor Stefan Collini who edited C P Snow’s The Two Cultures for publication by Cambridge University Press in 1993 makes the point well in his insightful introduction:

“In the second half of the nineteenth century, in the heyday of the scientistic aspiration, this could mean discriminating those enquiries whose methods gave us “real” knowledge from those which did not. Many practising scientists continue implicitly to endorse this assumption, and occasionally a self-appointed spokesman for science will articulate it in its most arrogantly imperial form” (p. xlvi)

When I encounter scientists who fall into this category I often suffer subliminal flashes of three historical groups: Roundhead soldiers smashing centuries of mediaeval heritage, barbarian crusaders disgracing themselves at the Ottoman Court, and Viking raiders. The Roundheads had moral certitude on their side. The crusaders had it too, and rampaged through more sophisticated cultures to which they believed themselves superior. And the Vikings also had at their disposal a new and superbly successful method for discovering things – the longship. They had a strong culture and made great contributions to world literature. But as the art historian Sir Kenneth Clark wrote of them:

“…one must admit that the Norsemen produced a culture. But was it civilisation? The monks of Lindisfarne would not have said so, nor would Alfred the Great, nor the poor mother trying to settle down with her family on the banks of the Seine.”

“…one must admit that the Norsemen produced a culture. But was it civilisation? The monks of Lindisfarne would not have said so, nor would Alfred the Great, nor the poor mother trying to settle down with her family on the banks of the Seine.”

When I see the longships of scientific imperialism nosing upstream, I do not think that what I am witnessing is the arrival of civilisation, nor even 50% of a thing called “culture”, but one rich, powerful - and therefore occasionally dangerous - contributor to the way we live and think.

But - partly, perhaps, because they are compensating for the chip on their shoulder - scientists too often present an embarrassingly swaggering, hairy-arsed arrogance to the world. They often pretend to believe (and some perhaps do) that science is not only the most powerful way of investigating the natural world – but the only valid way of looking at it - or indeed at anything else.

This is destined to alienate people who might otherwise be their friends and helpers. The wider practical consequences of this blinkered worldview will be explored in Fit the Second.

Envoi

A good friend of mine, the distinguished geologist Prof. Richard Selley of Imperial College London, once wrote: “All generalisations are dangerous – including this one”.

This does not mean that generalisations are not useful – it is a warning lest some idiot think that they apply universally. Scientists are not the Snow-white sepulchres of The Two Cultures, any more than they all resemble over-indulged - or borderline autistic - children (though a few come pretty close).

All the best clichés are rooted somewhere in truth. And the truth is that all professions favour people with certain personality characteristics. It is hard, for example, to believe that you can ever be a really good journalist if you are not a gossip. Conversely, there are plenty of professions where being a gossip would be a distinct drawback.

Scientists share, to a greater or lesser extent, many unique and enviable characteristics of mind – characteristics that in other circumstances might be defects, but which to a scientist are very positive indeed. Rather than pretend to be ordinary folk, scientists must recognise these and be proud. However, these characteristics, combined with the sociology of the scientific community, lie at the root of that community’s frequently expressed dissatisfaction with the way it is regarded by the non-scientific world. They are also the very factors that prevent scientists from reaching the level of self-awareness required for them to understand why they have only themselves to blame for this.

There has been quite enough bootless whingeing from scientists about how everyone is against them (an unsceintific assertion for which there is nothing but negative evidence - see Fit the fourth), and how others must change their ways to suit them.

Worse, innumerable, useless and expensive initiatives, mostly from government but some also from industry and its collectives, have managed a wonderful combination of squandering resources while raising false hopes. Far from improving matters, and while other folk just got on with the real job of communicating the excitement and sheer beauty of science to a wider audience, we have somehow given birth to a futile and increasingly self-serving Public Understanding of/Engagement with Science industry. This has dragged in conference organisers, pollsters, PR companies, Government departments, scientists themselves and their learned societies, until it has become the Tanganyika Groundnut Scheme de nos jours.

But that is for another Fit. Let me conclude this Fit with a general principle. Only when scientists accept that they are not just like everyone else and come to terms with it, will they also be able to come to grips effectively with what afflicts them.

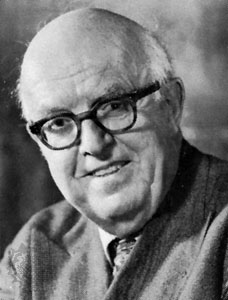

While assembling the ideas for this blog, my working title for it was The Three Cultures – to echo the famously titled The Two Cultures... the oft referred-to but almost completely unread 1959 Rede Lecture by novelist, scientist and statesman Charles Percy Snow. For it was with this document that angst about "science and the public", not to mention the whole useless, corrupt, self-serving circus that has since grown up about it, was first conceived.

While assembling the ideas for this blog, my working title for it was The Three Cultures – to echo the famously titled The Two Cultures... the oft referred-to but almost completely unread 1959 Rede Lecture by novelist, scientist and statesman Charles Percy Snow. For it was with this document that angst about "science and the public", not to mention the whole useless, corrupt, self-serving circus that has since grown up about it, was first conceived. In this he was undoubtedly right. But Snow’s caricatures - and the tendentiousness of his assertions and examples - seem absurd today. His portrait of the typical scientist (born in the progressivist atmosphere of the 1930s) puts one uncomfortably in mind of a Leni Riefenstahl propaganda film on the one hand and an issue of Health and Efficiency on the other. Scientists, said Snow, are “steadily heterosexual” folk displaying great moral health, who put the collective welfare of humanity first, and who apply their commonsensical materialistic view to bettering the lot of the underprivileged.

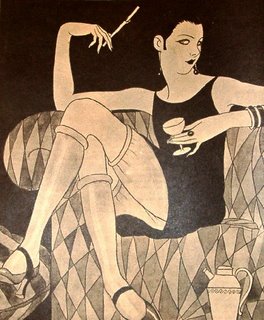

In this he was undoubtedly right. But Snow’s caricatures - and the tendentiousness of his assertions and examples - seem absurd today. His portrait of the typical scientist (born in the progressivist atmosphere of the 1930s) puts one uncomfortably in mind of a Leni Riefenstahl propaganda film on the one hand and an issue of Health and Efficiency on the other. Scientists, said Snow, are “steadily heterosexual” folk displaying great moral health, who put the collective welfare of humanity first, and who apply their commonsensical materialistic view to bettering the lot of the underprivileged. Literary intellectuals on the other hand, come straight out of Proust; all rouge, absinthe and cocktail cigarettes. Literary men (Snow’s world is almost exclusively masculine) had more of the “feline and oblique” about them, he wrote (1956). They cared more for themselves and their small coteries than for the world as a whole. They sniffed superciliously about what they saw as the empty materialism of technological progress, while more than half the world starved and could not afford such nose-holding.

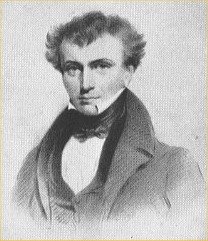

Literary intellectuals on the other hand, come straight out of Proust; all rouge, absinthe and cocktail cigarettes. Literary men (Snow’s world is almost exclusively masculine) had more of the “feline and oblique” about them, he wrote (1956). They cared more for themselves and their small coteries than for the world as a whole. They sniffed superciliously about what they saw as the empty materialism of technological progress, while more than half the world starved and could not afford such nose-holding. The reason lies in a neat example of how words and ideas do not exist independently (a theme I shall return to frequently in this blog, I feel sure). The terms “science” and “scientist” - meaning the pursuit of factual knowledge of the natural world and one who seeks it - were given to the English language by the 19th Century Cambridge polymath William Whewell (1794-1866). We now suffer a semantic distinction in English that simply does not apply in the rest of Europe, where the term “science” or its equivalent tends more to refer to all forms of organised knowledge. But even this is not the whole story. The strictures of Anglophony are as nothing compared to those of Britishness. For, just as academics are nearly always worse communicators than industrial scientists (who are trained to do it well because it means money), there is hardly any innate quality predisposing scientists to being poor communicators that is not hugely exacerbated by being British.

The reason lies in a neat example of how words and ideas do not exist independently (a theme I shall return to frequently in this blog, I feel sure). The terms “science” and “scientist” - meaning the pursuit of factual knowledge of the natural world and one who seeks it - were given to the English language by the 19th Century Cambridge polymath William Whewell (1794-1866). We now suffer a semantic distinction in English that simply does not apply in the rest of Europe, where the term “science” or its equivalent tends more to refer to all forms of organised knowledge. But even this is not the whole story. The strictures of Anglophony are as nothing compared to those of Britishness. For, just as academics are nearly always worse communicators than industrial scientists (who are trained to do it well because it means money), there is hardly any innate quality predisposing scientists to being poor communicators that is not hugely exacerbated by being British.